Housing and Environmental Justice: An Interview with Brenda Watson

Feb 12, 2025

In the third installment of our ongoing Housing and... series, we examine how housing intersects with environmental justice, sustainability, and energy equity—and why safe, stable, and efficient homes are critical to community well-being.

“Housing and…” is CHFA’s ongoing interview series that explores how housing intersects with and influences key sectors that shape our communities, including health, education, economic opportunity, and more. Each installment features insights from thought leaders, highlighting the critical role housing plays in shaping broader societal outcomes.

In this installment, we turn our attention to environmental justice as we talk with Brenda Watson, a leader known for her work at Operation Fuel and now as the Executive Director of the North Hartford Partnership. Brenda has long been at the forefront of energy equity. In this conversation, we’ll hear her insights on how affordable housing can promote energy efficiency, reduce environmental burdens, and foster community resilience in the face of climate change.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Marcus Smith: Your career has spanned leadership roles in energy equity and community development. Could you share a bit about your journey? What first inspired your work in environmental justice and sustainability, and how did housing come to play a central role in your vision?

Brenda Watson: I had always wanted a career in public service. After college, I was determined to come back home and make a difference in my community. My trajectory into energy and environment was really just about responding to the needs of folks who are struggling with the rising cost of energy and wanting to figure out a way to eliminate that as an issue. I began with direct service work, supporting at-risk youth. Over time, my career evolved into managerial roles, eventually leading me to Operation Fuel—an organization focused on providing energy assistance grants to people struggling with home energy costs.

There were three programs that I was most proud of establishing during my time at Operation Fuel, each geared to addressing unmet needs in the system. The first was the creation of Connecticut’s first statewide water utility assistance program-- because while people can live uncomfortably without heat or electricity, they absolutely cannot live without water.

I also developed the Homeless Intervention and Prevention Program aimed at reaching people as they were transitioning out of homelessness. I learned through program partners that often an unpaid utility bill could be enough to prevent folks from moving into stable housing.

The third program, inspired by Connecticut Children’s Healthy Homes, was the Better Homes and Buildings program. Health and safety issues like lead or mold can be barriers to weatherizing homes. The Better Homes and Buildings program filled the gaps between various programs and caught folks who would typically not be served by any other state or federal program.

MS: Terms like “environmental justice,” “sustainability,” and “energy equity” are increasingly part of our housing conversations. How do you define these concepts in the context of affordable housing?

BW: I define environmental justice and sustainability and energy equity as interconnected goals that create tangible benefits. These include deploying clean energy technologies and justice for the communities as a pathway to community development without displacement.

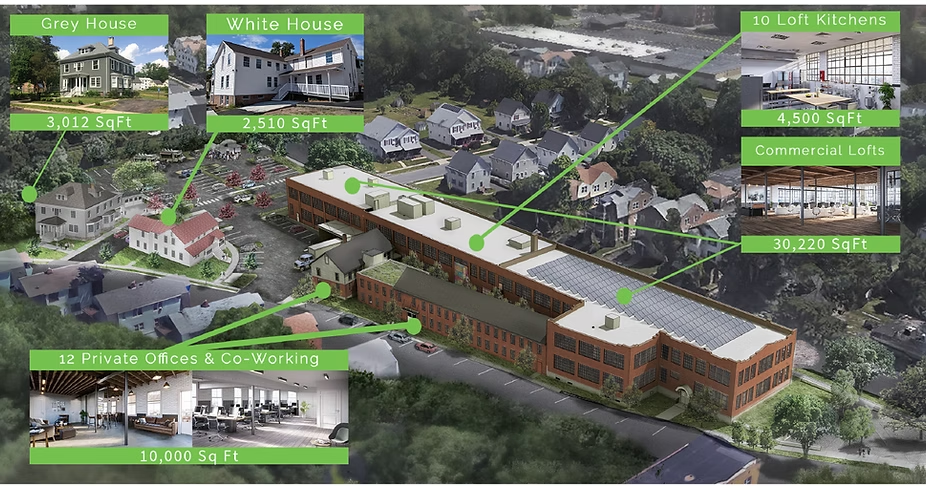

One way to contextualize this is through the work we’re doing at the North Hartford Partnership. We manage the Swift Factory, an 80,000 square foot commercial space with reduced rents that help folks who live in the community to start or scale their business. The Swift Factory serves as a platform for working with the community to help it get closer to net-zero, as a meeting space for residents to come learn about energy efficiency programs.

Aerial photo of Swift Factory Courtesy: North Hartford Partnership

We also own and manage multifamily properties in the neighborhood, so we have a vested interest in affordable housing that is energy efficient, so occupants are likely to use less energy, thereby reducing their energy burden. It’s also critical to improving indoor air quality. Implementing environmental justice policies can help stabilize housing for renters, reducing forced moves and promoting greater family stability. And for homeowners, the ability to make clean energy upgrades enhances resilience and probably adds a little bit of equity, too.

This approach supports long-term stability while also addressing the historical inequities that exist in North Hartford.

MS: As practitioners, we’re always on the hunt for best practices. Can you share examples of communities that you believe exemplify the intersection of housing, sustainability, and environmental justice? Who’s getting it right, and what are they doing differently? What lessons can we learn from these models?

BW: A couple of things come to mind. The first is Babcock Ranch, a community just outside of Fort Myers, FL known for its commitment to sustainability and resilience. The vision came from Syd Kitson, a former professional football player turned real estate developer. Syd felt that developers need to mitigate their impact on the environment. As a result, Babcock Ranch uses nature to divert water runoff to mitigate flooding. Buildings were designed to Green Building Coalition green home standards which include wind resistant concrete and windows. Babcock Ranch has also been dubbed America's first solar city as its two solar farms generate 150 megawatts of electricity – that’s enough to power 30,000 homes!

Solar farm at Babcock Ranch, FL | Source: www.babcockranch.com

The lesson for me is that private development has an impact on environment and communities and of course people. I’m sure Syd had quite a few obstacles, folks thinking that he was crazy, but he got it done. And this was back in 2006—a time when only those who were well off could afford to install clean energy tech.

Puerto Rico’s recovery effort after Hurricane Maria offers some lessons, too. Solar and backup storage installations significantly mitigated damage during subsequent storms. Sadly these are not examples that we often hear about in communities like North Hartford, which is really what I would love and what I'm working towards.

MS: In the case of Puerto Rico and Hurricane Maria, it took a major catastrophe to deploy the installation of these technologies. It might be more effective to be proactive and not wait for that massive storm to completely knock us out before we rebuild?

BW: Right. It's about rebuilding, but it's also important to be prepared in the first place. Our preparedness is not at a level which I feel good about. I think we're pushing up against a different time where natural disasters are occurring in ways that are just unfamiliar, unexpected. And we really do need to consider the resilience of all of our communities so folks are prepared and know what to do when disasters strike.

MS: It’s a common misconception that Connecticut is somehow immune—or at least MORE immune than other places in the US – to climate disasters like hurricanes or forest fires. But as seen with flooding that has devastated parts of Connecticut, including North Hartford, it’s clear that climate change is already here. How do you see affordable housing developers and funders stepping up to create climate-resilient communities?

BW: I feel like the funders have done a good job. From private foundations to the State of Connecticut to the federal government under the Biden administration, they have really responded to the issue in unprecedented ways. Developers are more challenged with making their projects energy efficient because it really boils down to dollars and cents for them. But it's a matter of educating developers about the value of green building practices and advocate for policies that incentivize these upgrades upfront.

For communities that are advocating for climate resiliency, it’s about asking the right questions. For example, if a grid goes down, how will residents in a multifamily building access critical systems like elevators? Resiliency and sustainability need to be built into every project, from codes to construction practices. There are ways of making climate resilient developments pencil out.

MS: For housing practitioners just beginning to engage with concepts like environmental justice or energy equity, where would you recommend they start?

BW: The mistake people often make is denying the community its voice. Do your reading, do your research. Understand the communities you're coming into and the work that people have done over the generations. I would start by reading the Jemez Principles of Democratic Organizing followed by an intense “undoing racism” training. There are other frameworks and strategies around a just energy transition that people can read so that they understand.

And for anyone interested in getting a start in the energy sector, you’ll do well as long as your heart is in the right place and you care about communities, climate justice, environmental justice, energy equity and justice – these are principles that can help redevelop communities.

MS: If you could change one thing in how housing intersects with environmental justice, energy equity and climate resilience, what would it be?

BW: Historically, when Black and brown communities focus on civil rights, it’s on issues like equal access to education and housing, or criminal justice reform. It’s like the environment as an issue has always been in the background, not quite at the heart of things. But in fact, Martin Luther King was instrumental in planting the seeds for environmental justice and ideas like land trusts as a means to rehab communities and push back against blight. Those initial ideas of his are just now coming to light.

If I could make one change, it would be in how disconnected these issues often seem, how people often miss how certain pieces intersect with each other. For so long, “caring about the environment” simply meant protecting animals and their habitat, or protecting trees. We need to get people to think about things differently.

If you care about treating and preventing asthma, you care about air quality -- and air quality is the environment. If you want to prevent pests in your home, composting is a great solution. That’s the environment, too.

When you begin to reframe these examples of everyday living, folks begin to realize “the environment absolutely does matter to me.”

That's the one thing that I would change: for folks to understand the impact our environment and our use of energy have on our everyday health and well-being, not to mention our pockets.

****

Marcus Smith is the Director of Research, Marketing, and Outreach at the Connecticut Housing Finance Authority (CHFA), where he helps drive statewide impact through data-informed strategies and compelling storytelling. With over two decades in mission-driven roles, Marcus has dedicated his career to expanding access to affordable, stable housing. His prior experience includes leadership in healthy housing initiatives at Connecticut Children's Medical Center and community development with Sheldon Oak Central. He holds a BA from the University of New Hampshire and an MBA from the University of Connecticut.